Just as most shark species must continually swim to pass water through the gills and oxygenate the blood, I am driven by a strong and mysterious force that keeps me seeking the most effective way to make positive change. My own nomadic blood has taken me on an incredible journey across five continents, over 20 different countries and four oceans on my quest to make a difference and live sustainably.

At some point during these adventures of searching for low impact living and eco-alignment I realised the irony of my situation. I was part of the nomadic travelling community creating huge demand for jet fuel and mass plastic packaging for all the single use products served on airplanes and in airports. There had to be a better way to journey without contributing so much to this totally unsustainable industry.

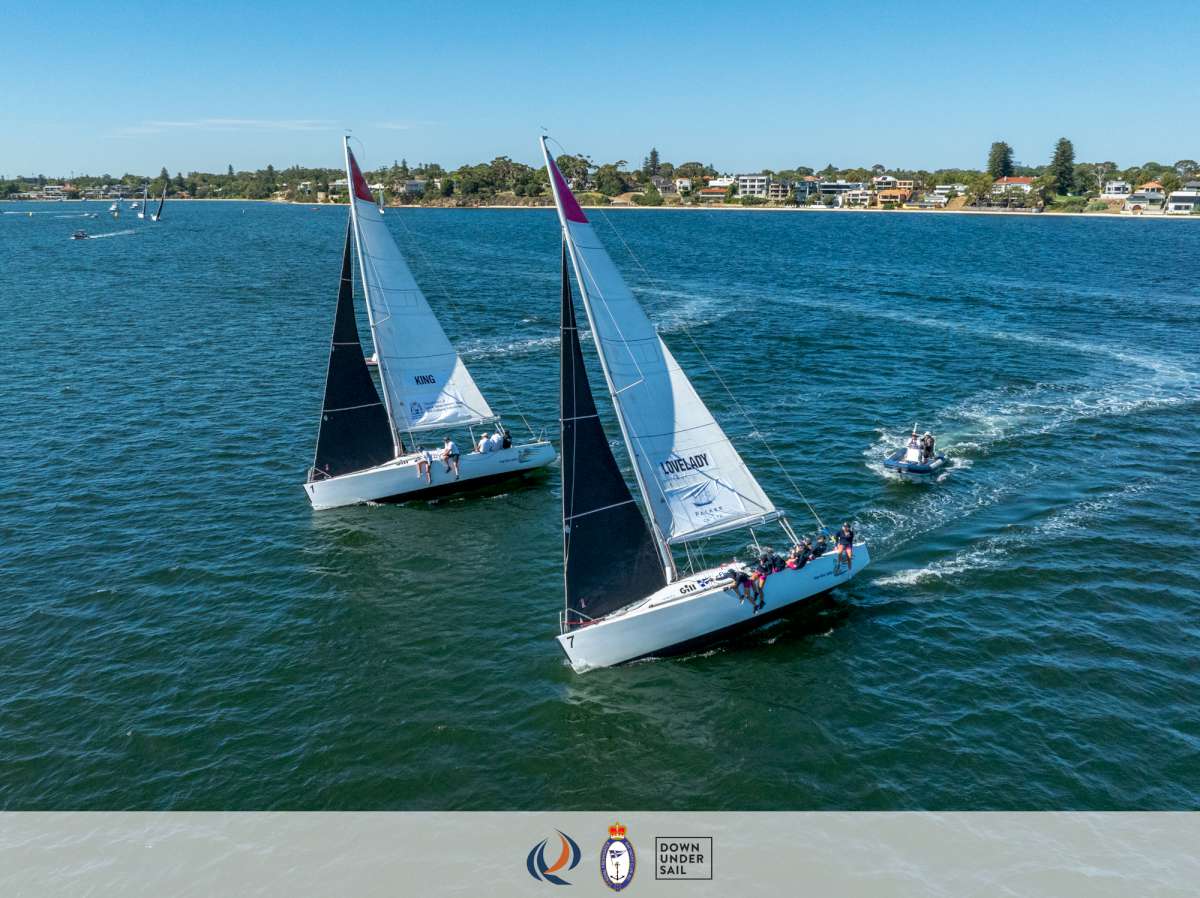

Late afternoon sessions sailing Hobie cats on Perth's Swan river with my dad when I was six or seven years old came to mind. The feeling of racing across the glimmering water by just the power of the wind was exhilarating and yet totally jet fuel free. Much of my adult life had revolved around water too and I had spent many years working on or skippering boats in various contexts.

After some substantial convincing, my non-sailing husband finally conceded and we begun our search for a suitable vessel. Surely living on a sailing boat and travelling by the power of the wind would be a much better option for us with our new baby.

It would give us a much more sustainable means to keep the water constantly flowing over our gills while, at the same time, it would provide us with a home, a place to raise our daughter and a place to cook. This is important to me as it has been difficult sourcing exclusively plant-based meals on our adventures while backpacking and at times had became a limiting factor of our travels.

After about six months, there was one boat that stood out and kept coming up in our conversations. We referred to it as ‘that little Spanish boat’ which seems a bit funny now as her generous 17 metre length often earns her a title as the biggest boat in the marina.

At the time we were toying with outrageous ideas such as building a 28m boat in ironwood from the Indonesian jungle with the traditional Phinisi style: an interesting combination of the Dutch influence and the local materials and skills. There were a few reasons we decided against the Phinisi, one of which being the obvious use of timber from very old trees. This, coupled with the maintenance of a wooden boat, the size which would require a regular crew, plus the tiny, insignificant matter of cost as we were totally broke!

Needless to say, the journey into boat ownership was a challenging one. ‘That little Spanish boat’ ended up being owned by a Swiss man and so, was not Spanish at all, although she was located in a picturesque seaside town on the southern coast of Spain.

Borrowing money from friends and family who believed in our dream and a substantial discount from Peter on the price, saw us as the proud owners of a 1967 De Vries 55. The sailing adventure had officially begun. Sustainability here we come, or so I thought.

Six months after purchasing Sama Sama I had given up using re-usable nappies for our daughter Gaïa as the constant task of hand washing allowed no time for anything else; it had become clear that life aboard was full of tasks that required endless amounts of time and money.

Our budget for life was limited and relied entirely on Sylvain’s modest salary from his online data recovery company. We figured we would be able to get by on this until I could find a way to generate a virtual income, by living mostly on anchor to avoid expensive marinas and keeping things simple. The reality was very different, we had become experts in reverse parking our temperamental long keel ketch into her tight marina berth with a crosswind. Sylvain steered using the emergency tiller arm, with me on the throttle while Gaïa loudly voiced her unhappiness by persistently screaming at me from her little pouch strapped to my chest.

Every time we took the boat out to get to know her better and prepare ourselves for our cruising lifestyle, hydraulic fluid would start squirting from the helm pump breather valve spraying oil all over the old teak floor of the wheelhouse. This released all the pressure in the hydraulic system so that the only way to get her back to the marina safely was to, once again connect the emergency tiller arm.

We were discouraged, exhausted, broke and fast becoming experts in Spanish wine to make ourselves feel better about the whole situation. The great thing about Spanish wine is that with a little knowledge of the grapes and the regions you can get a very nice bottle for only €5!

Troubleshooting the steering problem became a complex equation of rudder torque calculations, hydraulic fluid options, physical contortions of feeding mouse lines through awkward narrow places and the eventual replacement of the entire steering system. We ended up with a much larger brand spanking new Marsili cylinder and helm pump, all new lines, oils, joins and isolator valves. Luckily for us, Peter the kind and generous Swiss man who sold us the boat, refused to let us pay for the repairs, insisting that he wanted to give us a boat that worked and that would keep us safe.

With the same name and year of birth as my father, we connected instantly with Peter. Sharing a love of the ocean, exploring remote places and escaping traditional ways of life we adopted him as part of our family as he had never had kids of his own. His unwavering support of our choice to live aboard with our tiny baby and his constant overwhelming generosity helped us so much during that difficult transition into boating life. If it were not for him, I doubt we would have ever left that first marina.

Casting off our lines just as the sun made its first golden appearance on the horizon, I felt a mixture of exhilaration and trepidation. With Sylvain at the helm, I coiled the lines neatly on the deck and set about bringing in the fenders as I watched our home for the past six months sink further into the horizon behind our wake.

Finally we were at sea, maybe now I would have more time and could go back to the reusable nappies I thought; as well as trying to create an income, teach Sylvain to sail at the same time as learning the boat myself … It may seem obvious now, in hindsight, that maybe my expectations were somewhat unrealistic, but at the time I truly did think I could do it all with one hand tied behind my back while simultaneously trying to save the world!

I had grand ideas of monitoring plastic pollution, recording species sightings and starting my own global conservation organisation. Speaking of unrealistic expectations, I will take this opportunity to mention that the plan was to cross the Atlantic.

We would hop our way peacefully along the Spanish coast, day sailing between anchorages or marinas until we reached Gibraltar using the experience to get to know the boat, in replacement of actual sea trails due to the steering issue.

Then we would head down the Moroccan coast on the Atlantic side enjoying quaint fishing harbours and local culture along our way, eventually arriving peacefully in the Canary Islands. From there we would either choose to cross the 'pond’ directly or head to Cape Verde and then cross depending on time, weather and our feelings. Both Sylvain and I are very emotional creatures, often choosing a feeling or intuition over logic or seemingly more sensible choices.

Ultimately we planned to spend some time exploring the Caribbean and central America before finding a remote island in the South Pacific to live off the grid, barefoot and completely self sufficiently.

Just 17 nautical miles from our initial departure we reached our first stop. We jagged a great little spot to anchor in a protected bay between the marina and the fishing harbour.

After diligently checking the weather and exploring the little coastal town we agreed that we should stay for a week. We got good vibes and the anchorage was peaceful and protected from the notorious Mediterranean swell that often ruined a seemingly calm anchorage with its nasty short intervals. We had found, back in the bay near our initial marina, that even on the calmest of days with no wind, the anchorage could quickly turn from a dreamy, postcard perfect experience to an uncomfortable one of wild rocking and rolling. With just a couple of knots of wind in the wrong direction Sama Sama would sit at a perfect ninety degrees to the thirty centimetre high sets spaced exactly the right distance apart to keep her bucking from side to side wildly all night long.

After three blissful days in our new protected anchorage we finally began to relax and enjoy our cruising life. We were blessed with blue sky sunny days and we swam off the boat in the crisp cool water, rode the dinghy to shore to enjoy a cold cerveza or played with buckets of water on the aft deck with Gaïa.

We even had a go at setting up a back anchor to point us into the swell when the light winds did decide to turn us side on. It was nothing near as bad as our previous experience but we took the peaceful conditions as an opportunity to make ourselves as comfortable as possible and hone new skills.

In the afternoon on the fourth day at anchor we were drinking tea and chatting with a nice young couple we met on a nearby boat when the wind suddenly picked up. The forecast was for nothing more than ten knots for the next few days, but this was the forecast for the western Mediterranean.

We had not checked the local weather and later discovered that due to the coastal mountain range, wind funnels through between the peaks, causing strong acceleration zones. We were caught completely off guard with our back anchor out, side on to the now 40 knot gusts and being dragged straight towards the rock wall.

My previous experience skippering boats in fierce weather suddenly kicked in and I took charge of the deteriorating situation. Sylvain was more than capable and I left him to secure the deck while I put our extra two crew to work. The guy, I will call him Steve, was naïve but able bodied so I asked him to help Sylvain by hauling and securing the dinghies: ours and theirs, tied up alongside. His partner, I will call her Rebecca, seemed completely inexperienced with boating and quite frightened so I asked if she would mind to sit inside with Gaïa so that I could manage the boat. She was relieved and told me so.

I quickly set them both up in Gaïa’s little playpen/bed with toys and hurried back to the wheelhouse to start the difficult manoeuvre of bringing in the back anchor and then the main anchor to get ourselves clear of the bottom in time to avoid being smashed into the rock wall.

It had fast become clear that we would not be able to bring in the back anchor by hand with so much pressure from the increasingly frequent gusts. Sylvain tied a fender to the bitter end of the line so we could released the anchor and collect it later when the wind had died down. We set about retrieving the main anchor. With Sylvain feeding out the back anchor line to avoid getting it in the prop as I drove forward towards the main anchor and Steve on the bow to guide me, we began to retrieve the chain. As we moved away from the back anchor Sylvain let the fender go and we focussed on getting in our last anchor. I was able to retrieve a bit more chain before things went from bad to worse.

The angle of the wind and our dragging main anchor was blowing us back and we were drifting over our back anchor line. Having to keep the engine in neutral to avoid a prop wrap, I was unable to retrieve any more chain. Using only the bow thruster I eventually turned us just enough to get clear of the back line and put the engine in gear pulling up another two or three metres of chain before we ended up back in the same position. We continued like this for about half an hour, slowly moving closer and closer to the rock wall with each drift and then manoeuvering enough with the thruster to bring the chain in metre by metre. It was painstakingly slow and extremely stressful.

Eventually Steve was able to see the anchor but it was snagged on a bunch of discarded fishing lines and I could not bring it the last few metres. With the anchor now off the bottom our rate of drift towards the rocks was much faster. We needed to get free and fast. At this point my superhero husband grabbed a knife, made his way to the bow and cut us loose. With only a number of metres between us and imminent grounding we were finally free. Now all we had to do was reset the main anchor and we would be secure.

After two failed attempts to re-anchor it became clear that the wind was too strong and we would have to come up with a new plan. With our size and draft we were too big to go into the marina for safety and decided to try to find a place to tie up in the fishing harbour. I motored in to find only one possible place in an impossibly narrow spot in the corner of the harbour. I would estimate that the length of the makeshift berth was about 20 metres.

That gave me three metres of manoeuverability with a 40 knot crosswind and a very awkward angle. Our options were fast running out and exhaustion kicked in as this saga had been going on for over two hours now.

Somehow adrenalin kept me going and I attempted to get us alongside about five or six times. It was no use. The wind direction and angle of approach coupled with the small size of the space made it impossible for us to get in.

I drove Sama Sama out into a clear area in the middle of the harbour and assessed our options. We decided to drop Steve and Rebecca back to their boat which was much smaller and happily bobbing on its mooring buoy. They had been so helpful but it was time to let them get back to their evening. Then we headed back to try to anchor again.

When this failed as well, I made an emergency plan. I would come alongside one of the fishing boats, which were much bigger than Sama Sama. At least attached to them we would be able to catch our breath and make a better assessment of the situation before deciding what to do next. The sun had just set and now it was getting dark, as if we needed things to be any more difficult.

Luckily at this point the wind direction was in our favour and I was able to easily come alongside the largest of the fishing boats, which just happened to have massive cleats perfectly positioned for our lines. Before we could get any lines secured the engineer of the boat came running out of the wheelhouse yelling at us in Spanish and wildly waving his arms, signaling to us that we should not tie up.

I came out of our wheelhouse with Gaïa strapped to my chest and pleaded with him to allow us just a couple of minutes to rest as we had some problems and had nowhere to go. He noticed our Spanish courtesy flag and asked where we were from. In our broken communication we chatted with him and Sylvain managed to convince him to help us.

Suddenly his attitude changed and he came to our rescue. He told us we could tie up on the refuelling dock. That it was closed for the weekend because it was the Easter holiday and that he would call his friend who managed it to let her know so we would not get in trouble.

He even helped us fend off as we pulled away with the wind pinning us to his fishing boat, then ran around to the refuelling dock to help us with our lines.

We gave him a cheap bottle of Cava for his efforts, which he refused but I insisted. He could not have known the depth of our challenge over the past few hours, I really felt like he saved our lives that night.

After checking the lines and a few well earned shots of rum we all passed out and slept like babies.

Our steep learning curve had only just begun but we had come through this first challenge with no damage to ourselves or the boat. Little did we know that our challenges were only just beginning and that what had begun as an effort to live sustainably would end up being more of a fight for survival on the high seas.