It’s a big world. And 71% of it is salt water. But with more than 100,000 ships plying the oceans, it’s not unusual for a small sailboat to find itself in exactly the same piece of water as a “trading vessel”.

When that happens, the skipper or crewman on watch had better know his ColRegs, or large fines can be incurred. Worse, people could die.

There have been no published reports of Australian yachties being fined for breaches of the ColRegs recently, but there are plenty of examples overseas.

Champion solo sailor Marc Guillemot was fined £9,381 and costs of £4,125 for sailing the wrong way when crossing the Traffic Separation Scheme (TSS) in the Dover Straits in 2012 while taking part in the Around Great Britain and Ireland Race. (Australia has five TSS zones – two in the Bass Strait and one each in Port Jackson, Port Darwin and Botany Bay.)

However, Guillemot’s infraction was nothing compared to fellow Frenchman Antoine Koch who sailed his 60ft trimaran Sopra No 8 for 18 nm in the wrong direction in the same TSS. He met 21 vessels during the two hours he was in the wrong lane, causing seven of them to take evasive action. He was fined £15,000 and £2,600 costs.

Based on those fines, Paul Yates got off lightly when he was fined only £2000 for impeding the nuclear submarine USS Oklahoma City while it was under tow in the Solent. Yates was skippering a yacht for the first time and was in last place when he steered between the 360ft sub and the tug.

His excuse? “The sub didn’t stand up against the dark skies. They are painted to disguise themselves.” Apparently the two police launches accompanying the tow also failed to “stand up” despite displaying flashing blue lights.

But the daddy of them all has to be naval lieutenant Roland Wilson who became a YouTube sensation in 2011 when he decided there was room to sneak under the bow of the 120,000 tonne tanker Hanne Knutsen during Cowes Week. The pink spinnaker of his Corby 33 Atalanta of Chester hooked on the tanker’s anchor, bringing the mast down and seriously injuring one of Wilson’s crewmen. He was fined £100,000.

You can see the video on our website – www.mysailing.com.au/news/former-navy-officer-charged-after-yacht-hits-tanker-during-cowes-week

SYDNEY HARBOUR

In Australia, the most likely place for an incident between yacht and ship is Sydney Harbour. In fact, there have been so many incidents that NSW Roads and Maritime took action.

To run a yacht race on Sydney Harbour you need an Aquatic Licence and a condition of that licence will be that your Sailing Instructions state any competitor crossing within 200m of the bow of a trading vessel (which includes ferries showing an orange triangle) will be disqualified.

As I said, I couldn’t find any evidence of fines in Australia, but there have been several DSQs for the offence.

There will always be a skipper who thinks, ‘If I can get across the ferry’s bow, all the boats behind will have to go astern of it and I’ll open up a big lead.’

But it’s just not worth the risk – of a DSQ if a fellow competitor objects or the race committee sees you, or a collision like Lieutenant Wilson’s, or of the bureaucrats deciding to impose even more regulations or limiting the number of races allowed on the harbour.

MANLY FERRIES

The Manly ferries are the most likely vessels to cause problems for sailors – because of their size, speed and frequency. At 70.4m long and 1140 tonnes, the Freshwater class ferries travel at around 15 knots. When racing on the harbour it is quite common to see one ferry approaching from astern and another coming into view ahead.

Melwyn Noronha, Manager – Maritime Safety, Health, Environment and Quality for Harbour City Ferries says that generally people sailing on the harbour are very good but “occasionally we see people get in the way of ferries”.

He says it’s very important for sailors to know the routes of the ferries. “Around Fort Dennison where there is limited area, it can be difficult to manoeuvre the ferries, so we need sailors to be mindful. Also some of our faster vessels such as the river cat move at more than 15 knots and while they are manoeuvrable, they can’t stop dead in the water.

“It is similar advice to driving a car, you need time and distance to stop and it is the same for ferries. The faster they are the more distance they need to stop.

“When people are sailing up the river make sure you are highly visible. Sailing boats are not readily picked up on radar, so make sure you use lights at night and be especially careful around dawn. “

During particularly busy times, such as the Anniversary Day Regatta, the Sydney-Hobart start or on summer Sundays when the 18 footers are in full flight, the harbour is so crowded that most yachts should have one person doing nothing else but keep a lookout.

Obviously there are times when it is impossible for a yacht to get out of the way. During a “drifter” as often happens during the CYCA Winter Series or for the start of winter offshore races such as the Sydney-Gold Coast, yachts will be floating with empty sails while the ferry toots its horn and tries to take evasive action. The sailors can’t start their engines because they are racing and can’t conjure wind from no-where.

Of course, the ferry v sailboat battle is not just confined to Sydney Harbour. Pittwater can be crowded during weekends and there is a ferry that plies a course to Woy Woy. At Hamilton Island Race Week, the ferry from Airlie Beach often has to work its way through a fleet battling the Dent Channel tide. In WA the Rottnest ferry can be a regular nuisance and it is even possible to have an encounter when sailing a Hobie Cat near the Narrows Bridge in the centre of the city.

Basically, anywhere ferries run and yachts race, the skipper and crew need to be aware of their responsibilities or there will be more government intervention.

BIG SHIPS

There was a famous encounter between the 18ft Skiff Smeg and a huge tanker on Sydney Harbour a few years ago. Anyone who has sailed up the east coast has been amazed (or appalled) by the number of anchored ships off Newcastle. Even in the small WA town of Esperance on WA’s south coast, I can remember a close encounter with a bulk ore carrier inside the harbour when racing on a Beneteau 40.7.

With trade in coal, iron ore, wheat and other commodities booming, huge ships can be found entering and leaving ports all around our coast.

A harbour pilot once told me that yachties need to be aware of the restrictions imposed on the skipper or pilot. As the illustration shows, a 1188ft bulk carrier can have a blind spot of more than 600m below the bow.

“It’s like the signs you see on big trucks. ‘If you can’t see my wing mirrors, I can’t see you.’ Well, if the sailor can’t see the bridge, then the bridge can’t see the yacht,” the pilot said.

At night, the problem is compounded. In 2009 I was sailing solo around Wilson’s Promontory at 4am. My AIS showed 17 ships rounding the corner. Most were obviously going to miss me but there was one, identified as being 923ft long and heading for Singapore, that was coming straight for me. I could see both the green and the red nav lights.

I called the ship on VHS and got no answer. At this stage, calculating distance and speed, it was four minutes from hitting me. I called again. This time an excited voice answered: “You off port bow?”

“No,” I said as calmly as I could, “I’m directly in front of you.”

“Is all right,” said the voice. “We have you on radar. We miss you.”

The ship changed course slightly to port, perhaps lending a lie to that final sentence, and passed astern. I was in an aluminium yacht with a very good radar image. A fibreglass boat might not have showed so clearly.

DREDGES

Finally, it is not just ships and ferries that pose a problem. The sailing world was shocked in June of this year when a 57-year-old British woman, Bernadine Ingram, drowned after the yacht she and her partner were on hit a dredge at 1.30 in the afternoon in good visibility and immediately sank.

If you think that oil tankers and Manly ferries have trouble manoeuvring, imagine what is happening on a dredge that is effectively anchored to the bottom.

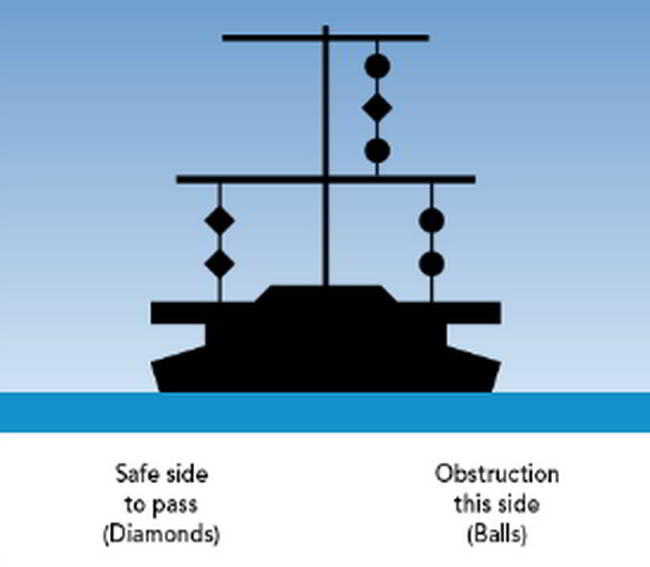

The rules are very simple, as the illustrations below show. Pass to the side showing diamonds. If you go on the side showing balls, at best you could get a yacht full of sand.

As with all matters nautical, there are some simple ways to stay safe and keep the regulators off our backs. You’re the skipper, you’re responsible. Keep a good lookout at all times. And don’t be complacent about the “power gives way to sail” rule.

Let me leave with you with a piece of doggerel which encapsulates the situation:

This is the grave of Mike O’Dea

Who died defending his right of way.

He was right, dead right, and his case was strong

But he’s dead just the same as if he’d been wrong.

Passing a dredge:

The blind spot:

This article was first published in the August-September 2014 issue of Australian Sailing + Yachting.